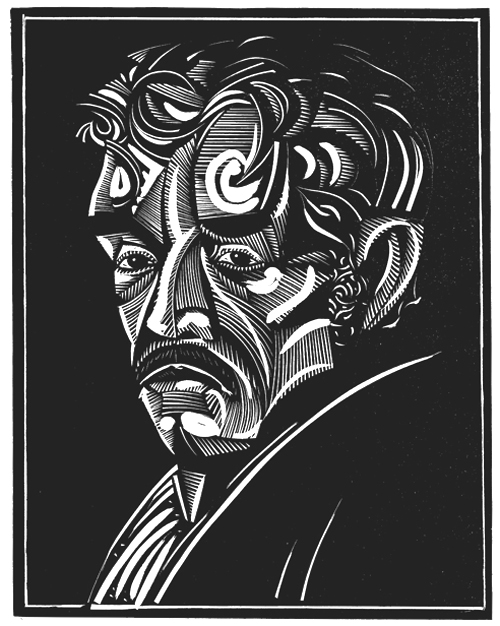

As part of my summer course work finishing up PDP at SFU, I took an eight-credit Designs for Learning Language Arts course with Dr. Carolyn Mamchur – to this date one of the most intelligent, warm and inspirational people I have yet encountered – during which each student was to study their favourite author. Since declaring English as my major some five years earlier, I had “belonged” to several authors: Wordsworth, Hesse, Hemingway, Whitman, Coupland, and even John Krakaur. But by the time of my course with Carolyn, I was enthralled by both Bob Dylan and Gabriel Garcia Marquez. Each’s obsession with magic and the ethereal nature of their art absorbed me that summer to the extent that I wrote a short novel during those months with characters who lived at the corner of streets named Zimmerman and Gabo in homage.

One of the projects I was to undertake as a final assessment for the Mamchur course was an address as Garcia Marquez, a daunting task given the ability of his writing to somehow encapsulate all of man’s experience on earth: sadness and joy, nostalgia and exaltation, death and birth. Below is the text of my speech, which I delivered along with slips of paper sporadically given out to the members of my class. To date it is the last university assignment I have completed, and one of my favourite pieces of creative writing, even though many of the best phrases are stolen (with credit given – though something has happened to some of the footnotes…) from the master.

Marquezologueþ

We all must end up here, where the light of the day dissipates and congeals, and we are separated from our memories, taken from this life. Many people survive on the thought that they will avoid this moment somehow, that through certain actions or words life might spare them a death filled with abject horror. I count myself among those who have wished that this were not the truth of living, who have asked to what end I have been sequestered here in an absurd fear, and in many ways I have generated my life as if perpetually facing this final scene. I have sought to see the world from a place outside of time, for it is our brief lives which are responsible for our obscured view of the truth. From a simple desk, with its wide surface and view of the sea through the brass-fit framed window, I have tried to touch this death where memory is stolen from us, committing myself to paper and ink as a means of final survival.

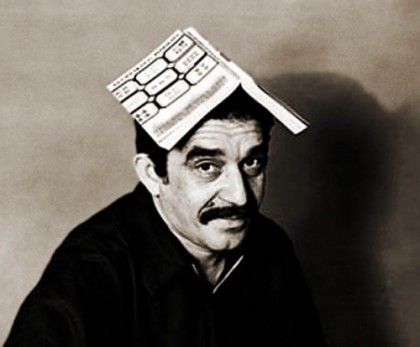

For years now many people have assumed that I have given more to my vocation than a commitment to the long patience of creation. My name is seldom mentioned without the epithet of magical, or fantastic, and to those outside my immediate circle of family and close friends I am no doubt seen as something more than a man who spends his time alone with his books. People do not want to believe that I have made my work the act of sitting behind my desk for the longest of hours, smoking cigarettes end to end – addicted as I am to the sensation of inhaling the same smoke, over and over again, until I die – scribbling with pens and variously typeset keys. They have always supposed that there has been something unreal behind the work spaces – collectively known to my family as the Caves of the Mafia – I have etched into each of my homes. It is a very human unwillingness to see the words of a page and assume them supported by nothing more than a man at his desk, filling pages with combinations of the letters. As if the lack of magic in a piece of artwork or moment in life would not be the utmost fantastic!

I should confess though that as a young man I had dreamed the life of a writer to be so many other things. By the age of twenty-five I had followed Hemingway to Europe, along with the romantic idea that I had somehow already achieved a literary immortality (in the brief run of daily newspaper columns that amounted, really, to nothing). I had just dropped out of the faculty of law after six semesters devoted entirely to reading everything I could get my hands on and reciting from memory the unrepeatable poetry of the Spanish Golden Age. I had already read, in translation, and in borrowed editions, all the books I would have needed to learn the novelist’s craft, and had published some stories in newspaper supplements that had won the enthusiasm of my friends and the attention of a few critics. The month before I was to turn twenty three, I had passed the age of military service and was a veteran of two bouts of gonorrhea. Every day I smoked, with no foreboding, sixty cigarettes made from the most barbaric tobacco, sleeping with the best company wherever I found myself at night. What more could I have wanted?

I should confess though that as a young man I had dreamed the life of a writer to be so many other things. By the age of twenty-five I had followed Hemingway to Europe, along with the romantic idea that I had somehow already achieved a literary immortality (in the brief run of daily newspaper columns that amounted, really, to nothing). I had just dropped out of the faculty of law after six semesters devoted entirely to reading everything I could get my hands on and reciting from memory the unrepeatable poetry of the Spanish Golden Age. I had already read, in translation, and in borrowed editions, all the books I would have needed to learn the novelist’s craft, and had published some stories in newspaper supplements that had won the enthusiasm of my friends and the attention of a few critics. The month before I was to turn twenty three, I had passed the age of military service and was a veteran of two bouts of gonorrhea. Every day I smoked, with no foreboding, sixty cigarettes made from the most barbaric tobacco, sleeping with the best company wherever I found myself at night. What more could I have wanted?

For reasons of poverty rather than taste, I had anticipated what would be the style in twenty years time: untrimmed moustache, tousled hair, jeans, flowered shirts and a pilgrim’s sandals. In a darkened movie theatre, not knowing I was nearby, a girl I knew told someone: ‘Poor Gabito is a lost cause.’

But I already did not belong to that same world as was attempting to grade my successes. My wardrobe and carousing of those days spoke to the fondness I had begun to hold for George Bernard Shaw’s declaration that, From a very early age, I have had to interrupt my education to go to school. As the acquaintances of my youth and law school began to pull away into the shadows of financial and romantic security, I only continued to withdraw, along with several inseparable friends, living on essentially less than nothing, preparing to publish a radical new magazine. The desperation of each action in those days gave my life a sensation of vitality, and if you will excuse the expression, integrity. To the immense disappointment of my parents, I could have no more returned to my studies than I would have been willing to sacrifice my very soul.

My mother and I journeyed during this time in my early twenties to sell the house of my grandparents, where I had grown up until the age of eight. When she met me in the company of my friends, she mistook me for a beggar, and spent the balance of the trip urging me back into law school at the behest of my father, whom I had not seen in several months. On the returning train, she realized I was not asleep, and asked me: ‘What are you thinking about?’

‘I’m writing,’ I answered. And I rushed to be more amiable: ‘I mean, I’m thinking about what I’m going to write when I get to the office.’

‘Aren’t you afraid your papa will die of grief?’

I eluded the charge with a long pass of the cape.

‘He’s had so many reasons to die, this one must be the least fatal.,’ I said, though it was not the most propitious time for me to attempt a second novel, after having been mired in the first one and attempting other forms of fiction, with luck or without it, but that night I imposed it on myself like a vow made in war: I would write it or die. Or as Rilke had said: ‘If you think you are capable of living without writing, do not write.’

‘So what shall I tell your papa?’

Tell him I love him very much and that thanks to him I’m going to be a writer.’ Without compassion I anticipated any other alternatives: ‘Nothing but a writer.’ €€

It had begun six years earlier, when I had read Kafka and been struck as if by lightning. As Gregor awoke from unsettling dreams one morning, he found himself transformed in his bed into a monstrous vermin. He lay on his hard, armorlike back and when he raised his head a little he saw his vaulted brown belly divided into sections by stiff arches from whose height the coverlet had already slipped and was about to slide off completely. His many legs, which were pathetically thin compared to the rest of his bulk, flickered helplessly before his eyes. ≠

I had set out just like that, after reading The Metamorphosis, at eight o’clock the next morning, to find out what the hell had been done in the novel from the bible on up to what was being written at the time. For the next six years, I dropped out of studying. I dropped out of everything. Kafka had written a novel that opened the door to the possibility of a singular literary voice, the idea that with a long enough patience, new literature could still be contributed. Years later, when I would be months into the initial drafts of One Hundred Years Of Solitude, I was buoyed by the naïve confidence that in my dreams I was inventing literature.

At twenty three though, what can one know about motivations? I couldn’t conceive of a direction for my ambitions – I merely suspected that I was the master of my own destiny, and if I would declare that I was fearless loudly, it was to ward off the prospect of encountering my greatest of fears in truth and reality. On the trip with my mother, to sell my deceased grandparents’ home, I would encounter my own mortality in the vision of a crumbling house and decaying town, a realization so decisive that the longest and most diligent of lives would not be enough for me to finish recounting it. Now, with the sum total of my hundred years behind me, I know it was the most important of all the decisions I had to make in my career as a writer. That is to say: in my entire life€.

‘I’ve come to ask you to please go with me to sell the house.’

My mother did not have to tell me which one, or where, because for us only one existed in the world: my grandparents’ old house in Aracataca, where I’d had the good fortune to be born, and where I had not lived again after the age of eight. More than a home, the house was a town, hosting several sittings of each meal throughout the days that would end with a cocoon of hammocks struck up and upon one another in the courtyard.

But in those memories of my pre-adolescence, I was much more interested in the future than the past, and so my recollections of the town were not yet idealized by nostalgia. I remembered it as it was: a good place to live where everybody knew everybody else, located on the banks of a river of transparent water that ran along a bed of polished stones€, which were white and enormous, like prehistoric eggs. The world was so recent that many things lacked names, and in order to indicate them it was necessary to point. Every year during the month of March a family of ragged gypsies would set up their tents near the village, and with a great uproar of pipes and kettle drums they would display new inventions. First they brought the magnet. A heavy gypsy with an untamed beard and sparrow hands, who introduced himself as Melquiades, put on a bold public demonstration of what he himself called the eighth wonder of the alchemists of Macedonia. He went from house to house dragging two metal ingots and everybody was amazed to see pots, pans, tongs and braziers tumble down from their places and beams creak from the desperation of nails and screws trying to emerge, and even objects that had been lost for a long time appeared from where they had been searched for most and went dragging along in turbulent confusion behind Melquiades magical irons. ‘Things have a life of their own,’ the gypsy proclaimed with a harsh accent. ‘It’s simply a matter of waking up their souls.’ Œ

But in those memories of my pre-adolescence, I was much more interested in the future than the past, and so my recollections of the town were not yet idealized by nostalgia. I remembered it as it was: a good place to live where everybody knew everybody else, located on the banks of a river of transparent water that ran along a bed of polished stones€, which were white and enormous, like prehistoric eggs. The world was so recent that many things lacked names, and in order to indicate them it was necessary to point. Every year during the month of March a family of ragged gypsies would set up their tents near the village, and with a great uproar of pipes and kettle drums they would display new inventions. First they brought the magnet. A heavy gypsy with an untamed beard and sparrow hands, who introduced himself as Melquiades, put on a bold public demonstration of what he himself called the eighth wonder of the alchemists of Macedonia. He went from house to house dragging two metal ingots and everybody was amazed to see pots, pans, tongs and braziers tumble down from their places and beams creak from the desperation of nails and screws trying to emerge, and even objects that had been lost for a long time appeared from where they had been searched for most and went dragging along in turbulent confusion behind Melquiades magical irons. ‘Things have a life of their own,’ the gypsy proclaimed with a harsh accent. ‘It’s simply a matter of waking up their souls.’ Œ

I never thought it legitimate that life should make use of so many coincidences forbidden literature, and this thread of my appreciation for the mysteries of the world is often what is attached to my writing as surreal, or – that wicked title again – magical. I owe this sense of wonder to the tutelage of my grandmother, solely, who was seized by the feeling that there was a man bigger than all of us walking through the plantations while nothing moved, and everything seemed perplexed at the passing of that man£. She was a credulous and impressionable woman, in whom the mysteries of daily life struck much terror. She saw that the rocking chairs rocked alone, that the scent of jasmines from the garden was like an invisible ghost, that a cord dropped by accident on the floor had the shape of numbers that might have been the grand prize in the lottery€, and her influence peopled my reality with the silent stirrings of another world.

I left Aracataca at the age of eight and did not return for fifteen years. Though my parents had experienced the brief encounter with history that the town enjoyed – the result of a banana plantation which lasted until just before my birth – I grew up in a village from which the wider world was already in retreat. Ignorant of the erosion the place would see in my displaced years, my childhood home began to crystallize into gems of nostalgia I would take to be the truths of my life until many years later. The sensation of having survived on rations of so many false memories became the thriving current of my life, and I have become indebted to afternoons such as when my grandfather paid the thirty reales and we were led into the center of a tent, where there was a giant with a hairy torso and a shaved head, with a copper ring in his nose and a heavy iron chain on his ankle, watching over a pirate’s chest. When it was opened by the giant, the chest gave off a glacial exhalation. Inside there was only an enormous, transparent block with infinite internal needles in which the light of the sunset was broken up into colored stars. Disconcerted, knowing that children were waiting for an immediate explanation, my grandfather ventured a murmur: ‘It’s the largest diamond in the world.’

I left Aracataca at the age of eight and did not return for fifteen years. Though my parents had experienced the brief encounter with history that the town enjoyed – the result of a banana plantation which lasted until just before my birth – I grew up in a village from which the wider world was already in retreat. Ignorant of the erosion the place would see in my displaced years, my childhood home began to crystallize into gems of nostalgia I would take to be the truths of my life until many years later. The sensation of having survived on rations of so many false memories became the thriving current of my life, and I have become indebted to afternoons such as when my grandfather paid the thirty reales and we were led into the center of a tent, where there was a giant with a hairy torso and a shaved head, with a copper ring in his nose and a heavy iron chain on his ankle, watching over a pirate’s chest. When it was opened by the giant, the chest gave off a glacial exhalation. Inside there was only an enormous, transparent block with infinite internal needles in which the light of the sunset was broken up into colored stars. Disconcerted, knowing that children were waiting for an immediate explanation, my grandfather ventured a murmur: ‘It’s the largest diamond in the world.’

‘No,’ the giant countered. ‘It’s ice.’Œ Œ

During the two days I would spend in Aracataca with my mother, I reencountered the streets of my lost youth, gripped in the endless haze and heat of its eternal siesta since the banana company’s departure some twenty five years earlier. The exodus had left the town in the fearful whirlwind of dust and rubble being spun about by the wrath of a biblical hurricaneŒ. It was as if there had been a fearful dry storm of volcanic thunder and lightning and the awesome polar wind which had turned the bowels of the sea upside down and carried off an animal circus set up on the square of the former slave port where for weeks afterwards men caught elephants in casting nets, drowned clowns and giraffes hanging on trapezes from the fury of the tempestæ.

In the heat of that first dusty afternoon it was as if we were also seeing that the sea had also been stolen, including not only the physical waters visible from our window to the horizon, but everything that was understood by sea in the broadest sense. The flora and fauna belonging to the water, its system of winds, the inconstancy of its millibars, everything. I could never have imagined that they would have been capable of doing what they did to carry off the numbered locks of our old checkerboard sea with gigantic suction dredges, and in its torn crater we could see appear the instantaneous sparkle of the submerged remains of the very ancient city of Santa Maria de Dareien, laid low by the whirlwind. We could see the flagship of the first admiral of the ocean sea, just as I had once seen it from my window, identical, trapped by a clump of goose barnacles that the teeth of the dredges had pulled out by the roots before we had time to order an homage worthy of the historic importance of that wreck. They carried off everything that had been the reasons for our wars and the motivations for our power and left behind only the deserted plain of harsh lunar dustæ that was my first encounter with the immediate weight of death. Until then, I had conceived of death as a misfortune that befell others, other people’s fathers and mothers, other people’s brothers and sisters and husbands and wives, but not my own. I was at the time a person whose life was slow, who did not see myself growing old, or falling sick, or dying, but now was someone who would disappear little by little in my own time, turning into memories, mists from other days until I would be absorbed into oblivion. Œ

Each thing, just by looking at it, aroused in me an irresistible longing to write so I would not die. I had suffered this on other occasions, but only on that afternoon did I recognize it as a crisis of inspiration – that word, abominable but so real, that demolishes everything in its path in order to reach its ashes in time. Standing in the room in which I had been born, scorching in the stillness of the afternoon heat, I examined the room with the clairvoyance of my last days and for the first time saw the truth: the final bed, the pitiful dressing table whose clouded, patient mirror would not reflect my image again, the chipped porcelain washbasin with the water and towel and soap meant for other hands, the heartless speed of the clock racing toward the unelectable appointment on my final afternoon. I crossed my arms over my chest and began to hear the radiant voices of the slaves singing the six o’clock salve in the mills, and through the window I could see the diamond of Venus in the sky that was dying forever, the eternal snows, the new vine whose yellow bellflowers I would not see bloom on the following Saturday, in the house closed in mourning, the final brilliance of life that would never, through all eternity, be repeated again∏.

In the light of that August afternoon began a period where I wrote down everything I thought, everything I knew, writing on pieces of cardboard that I would tack behind the toilet, writing down the few things I remembered to make sure that I would never forget them. I wrote down signs which would seize me on the yellow ledger margins that I would roll like cigarettes and hide in the most unlikely chinks in the house where only I would be able to find them in order to remember who I was when I would no longer remember anythingæ. Which is where I find myself at this moment, in the spilling purgatory of death, where so begin to erode my monuments of words, written over the past fifty years with only the most selfish of intentions: to steel myself against the natural ravages of time, and to enjoy during the brief course of my life a dialogue with those pieces of myself many people would ignore or otherwise take for granted. In the course of my many years I have learned that Life is indeed not what one has lived, but what one remembers, and how one remembers it in order to recount it. My youth, dreams and grim nostalgia which compose my soul and which will now dissipate in the swells of time have taught me that there might be no other village, nation, or universe except the one I could create in my own image and likeness, where space was changed and time corrected by the designs of my absolute willæ. I have only ever sought to achieve this experience in the effort of establishing a solidarity with the people of my home.

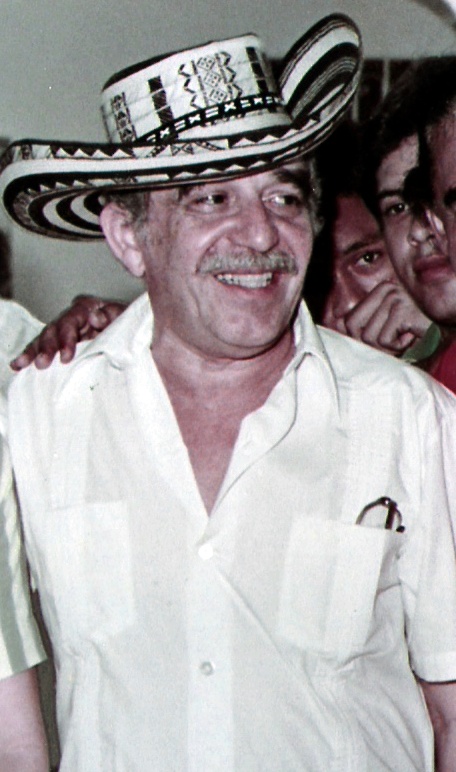

I have written so that upon my departure, the people of Macondo will hold their breath for the fraction of centuries my body will take to fall into the abyss, so that they will not need to look at one another to realize that they will no longer be all present, that they never will be. But they will also know, in this, my most personal of fantasies, that things will be different from then on, that their houses will have wider doors, higher ceilings, and stronger floors so that the memory of Colonel Aureliano Buendia might go everywhere without bumping into beams, and so that no one in the future would dare make disparaging remarks against either Florentino Ariza or Fermina Daza, because they will paint their house fronts gay colours to make the memory or Ursula Inguaren eternal, and they will break their backs digging for springs among the stones, and plant flowers on the cliffs so that in future years at dawn, the passengers on great liners will awaken, suffocated by the smell of gardens on the high seas, and the captain will have to come down from the bridge in his dress uniform, with his astrolabe, his pole star, and his row of war metals, and, pointing to the promontory of roses on the horizon, he will say in fourteen languages, Look, there, where the wind is so peaceful now that it’s gone to sleep beneath the beds, over there, where the sun is so bright the sunflowers don’t know which way to turn, yes, over there, that’s Gabito’s village£.

I have written so that upon my departure, the people of Macondo will hold their breath for the fraction of centuries my body will take to fall into the abyss, so that they will not need to look at one another to realize that they will no longer be all present, that they never will be. But they will also know, in this, my most personal of fantasies, that things will be different from then on, that their houses will have wider doors, higher ceilings, and stronger floors so that the memory of Colonel Aureliano Buendia might go everywhere without bumping into beams, and so that no one in the future would dare make disparaging remarks against either Florentino Ariza or Fermina Daza, because they will paint their house fronts gay colours to make the memory or Ursula Inguaren eternal, and they will break their backs digging for springs among the stones, and plant flowers on the cliffs so that in future years at dawn, the passengers on great liners will awaken, suffocated by the smell of gardens on the high seas, and the captain will have to come down from the bridge in his dress uniform, with his astrolabe, his pole star, and his row of war metals, and, pointing to the promontory of roses on the horizon, he will say in fourteen languages, Look, there, where the wind is so peaceful now that it’s gone to sleep beneath the beds, over there, where the sun is so bright the sunflowers don’t know which way to turn, yes, over there, that’s Gabito’s village£.

July 30th 2006

þ All works cited are those of Gabriel Garcia Marquez unless otherwise noted.

€ Living to Tell the Tale

≠ Kafka, Franz. The Metamorphosis

€ Living to Tell the Tale

ΠOne Hundred Years of Solitude

£ Leaf Storm and Other Stories

€ Living to Tell the Tale

ΠOne Hundred Years of Solitude

æ The Autumn of the Patriarch

∞ Love in the Time of Cholera

∏ The General in His Labyrinth

æ Autumn of the Patriarch

£ Leaf Storm and other Stories: “The Handsomest Drowned Man in the World”

One thought on “Marquezologue”

Comments are closed.