Teaching and learning in the open is wild. Anything can happen and hopefully it does…

We’re a few weeks into the open-online experiment that has been our school’s pilot Philosophy 12 course, enough time to pause and – yes – reflect on what has begun to emerge from the medium, course content, and individual voices and perspectives that are shaping the learning experience. Looking back on these first few weeks, here is what I’ve been discovering:

An open course revolves around its architecture

I’ve been lucky to have had the opportunity to work for a few years now in what amounts to a blended learning environment that incorporates blogs, wikis and class discussions; as well, I’ve also had the good fortune to meet and work alongside luminaries in the field of open education and digital course delivery. These experiences have led to focusing much of my September attention (when I haven’t been in the woods with my other classes) setting up the online environments and channels to enable and support the for-credit, face-to-face learners in our school, as well as allowing for straightforward channels of online participation for our open-online learners and facilitators.

This has largely centered around the creation of:

- A google form to sign up as a participant on the blog and in the course

- A course wiki to function as a digital accompaniment to the text

- A class blog to function as a conversation hub and resource-sharing area

- An RSS bundle of blog posts and comments to follow the discourse

- Broadcasting classes regularly on #ds106radio

Philosophy is about the Journey, not the Destination

More of a course outcome than something I’ve learned about online pedagogy, I was engrossed as the class spent much of its first few weeks setting out to define Philosophy along our own terms, incorporating different perspectives and readings as participants saw fit. This process revealed many different personal definitions of philosophy, and a working vocabulary for the community at hand which paid homage to Wittgenstein’s statement that:

Philosophy is not a theory but an activity.

The words we use are important

After wading into the process of conducting philosophy, the rest of the Wittgenstein quotation (shared as part of Kristina’s definition) becomes worthy of contemplation:

A philosophical work consists essentially of elucidations. The result is not a number of “philosophical propositions” but to make propositions clear. Philosophy should make clear and delimit sharply the thoughts which otherwise are, as it were, opaque and blurred.

To make propositions clear.

As we began, I quickly realized that this was no small task in a group of young intellectuals in love with language, performance, and the newness of many of their own emerging ideas. Our conversations over the course of the first week, and more than a few of the ensuing posts on the class blog, careened wildly from thoughts about life and death, the nature of reality, ethics and the various topics at hand. The ideas were powerful, but fleeting – ethereal and never fully grasped before the next one had arrived.

Teaching and facilitating in this environment, and with the above-stated goal in mind, to meaningfully conduct philosophy rather than learn about it as such, involves (for me) a (hopefully) transparent positioning of myself in such a place that I can point out, or suggest different directions or aims of the various tasks the group is undertaking: instigating pauses, asking for more deliberate expressions or synthesis of ideas, creating space and time for reflection and, if necessary, gently directing that reflection.

Assessment opportunities frame the outcomes

This is a relatively fresh understanding beginning to emerge as the class has been delivering its first set of assignments which have ranged from news broadcasts and ‘human experiments,’ to stories, blog reflections and a formal debate. Here my thinking has been particularly influenced and aided by GNA Garcia, who has been an outgoing and supremely helpful co-learner, participant and facilitator in the #philosophy12 experiment, listening on the radio, offering links and related readings, asking questions, and sharing back-channel feedback and help from a course-design perspective.

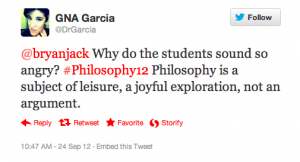

One question GNA tweeted yesterday during a broadcast of one group’s presentation of a formal debate led to much thought about the nature of assignments proposed within the course construct:

Upon further reflection and some conversation, this question about the tone (and objective) of debating itself led to much thought about another article GNA shared in a blog post wrapping up her first week ‘Back in Grade Twelve‘ by James Paul Gee entitled Beyond Mindless Progressivism. Gee outlines seventeen principles of course design and implementation that read like a laundry list of (personally) ideal classroom objectives, one of which I’ll bring out here:

Learners are well prepared to learn new things, make good choices, and be able to create good learning environments for themselves and others across a lifetime of learning.

This conversation addressed the intention of our learning community – to conduct philosophy – and the ability of our assignments to meet this expressed need. For me, teaching (or: facilitating the learning process around) learners “being able to create good learning environments for themselves‘ involves interrogating the ability of the assignments themselves to achieve course outcomes. Now, the particular assignment of the debate had been suggested by the group, but in allowing a learner-generated assignment model, the class as designed by the instructor/facilitator was, in this case, endorsing a mode of instruction and presentation not entirely suited to the stated goal of the course: to build ideas together rather than for one party’s ideas to emerge victorious.

“I am asking permission, really,” I told the class this morning after some thought, “If you all would be OK with me revising our assignment proposal sheet, not to limit the scope of assignments necessarily, but to encourage thinking toward what our purpose is here, and to reflect on how the assignments you choose to do support that goal.”

…the past is just the stuff with which to make more future.

Which is where we find ourselves today in Philosophy 12: figuring it out, sharing our thoughts and reflections on the process as it unfolds. We are paying attention, and trying to make some sense of it along the way.

As we live we learn.