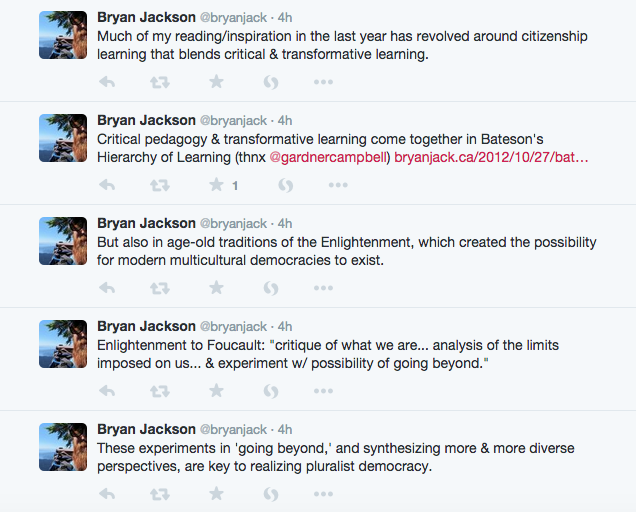

This is the sort of thing that might otherwise be relegated to an aggregated Storify or series of screenshots. But as this afternoon’s series of Tweets was intended to partially sketch out the main ideas in what will be a much larger – Master’s thesis-sized – work, expanding on some of these points seems well-suited to a longer look here on the blog.

While not generally considered the forum to share and discuss more substantial themes or ideas, I’ve noticed more and more of the people I follow using part of the natural functioning of Twitter to follow through with some of their longer-form thinking.

One of the pioneer’s of the form, Jeet Heer published a spin on one of his essays in the Globe and Mail last fall, noting this popular conception:

6. With strict 140-character limit & cacophony of competing voices, Twitter seems like worst place to write an essay.

7. To critics, a Twitter essay is like life-size replica of the Eiffel Tower made from chopsticks: perverse enterprise.

But he went on to enumerate the ways in which Twitter might be the perfect venue for such thinking:

14. With a properly focused topic, a set of tweets allows you to ruminate on a subject, to circle around it: to make an essay.

15. An essay in original French meaning of term is a trial, an attempt, an endeavour: a provisional thought about something.

16. At the very root of the essay form is its experimental and makeshift nature. An essay isn’t a definitive judgment but a first survey.

17. The ephemeral nature of Twitter gives it a natural affinity with the interim and ad hoc nature of the essay form.

18. A Twitter essay isn’t really an argument; it’s the skeleton of an argument.

19. Tweets are snowflake sentences: They crystallize, have some fleeting beauty and disappear.

20. To write snowflake sentences is liberating: They don’t have to have the finality of the printed word.

21. Fugitive thoughts quickly captured.

This last point may perfectly characterize the difficulty of attempting to synthesize what has been more than a year of wide reading on a variety of loosely interrelated topics, bound together in many ways only by my own ability to connect them (if this is truly the purpose of academic study): to begin to write about these readings and plot our next steps forward as a grad cohort, we are engaged in the pursuit of such fugitive thoughts.

As an exercise in collecting my thinking on a year’s work, I set out to form the basis of my thesis in a few posts:

While the ‘elevator pitch’ for the thesis begins in a few different places – critical pedagogy, Enlightenment thinking, or youth voter apathy – these ideas became today’s point of origin, and together might constitute something of an introduction to what I hope will serve as a research project.

While the ‘elevator pitch’ for the thesis begins in a few different places – critical pedagogy, Enlightenment thinking, or youth voter apathy – these ideas became today’s point of origin, and together might constitute something of an introduction to what I hope will serve as a research project.

It might begin something like this:

Citizenship in a pluralist democracy requires the cultivation of skills and dispositions that allow for an ongoing constructivism of more and more diverse perspectives within a collective identity. Multiculturalism is the natural extension of emergent epistemologies which draw on both critical and transformative pedagogies.

There are a number of scholars’ work who have led me to the drafting of such a sentiment, chief among them Deborah Osberg and Gert Biesta, Paulo Friere, and Gregory Bateson.

Osberg and Biesta’s inquiry into whether a truly emergent epistemology could be possible in schools has concerned a great deal of linked text published to this blog in recent years:

- Emergent Citizenship: Curriculum in the Digital Age

- Metaphysical Emergence & the Discussable Object

- Generative Themes, Emergent Subjectivities and the Discussable Object

Paulo Freire also figured largely – as he tends to – in my ongoing research into a pedagogy that might help bring about such an emergent constructivism:

- Design Thinking as Critical Literacy

- Limit Situations, Double Binds & Transformative Learning

- Liberation Citizenship for the 21st Century

And each of these threads culminates in the transcendent quality which Michel Foucault places in Enlightenment itself, which he called a “critique of what we are” and an “experiment” with going beyond the limits “imposed on us,” bringing about the paradigm shift which resets Freire’s critical praxis. Gregory Bateson (and Daniel Schugurensky) exnten this thinking and discuss the political and cultural necessity of working toward transformation as an ongoing process.

- Moments Happen Quickly and Changes Come Slowly

- Bateson’s Hierarchy of Learning

- An Ignite Talk: No Handbook for Transcendence

Here we might continue in an academic voice:

However, the public institutions charged with producing and maintaining a citizenry that values emergence, and practices critical transformation are caught in something of a paradox as they intend to produce something which necessarily must be composed out of a fluid and ever-changing constituency.

Not only are schools tasked with cultivating a curriculum which orients itself toward the production of that citizenry, but the broader socio/political/economic culture must be constantly reevaluating and defining just what that citizenship itself is seen to represent.

As institutions, they are faced with the reality of developing targets; yet a certain amount of recognizing aims within an emergent system means drawing the target around the shot that has been taken.

Within a Canadian context, a multicultural constitution creates the (apparently) unresolvable tension between inviting and encouraging greater and greater diversity along with the generation of unifying symbols and experiences. A multicultural nation is one that is perpetually becoming, making the notion of citizenship (not to mention the form and function of the institutions charged with imbuing the younger generation with a sense of that citizenship) elusive.

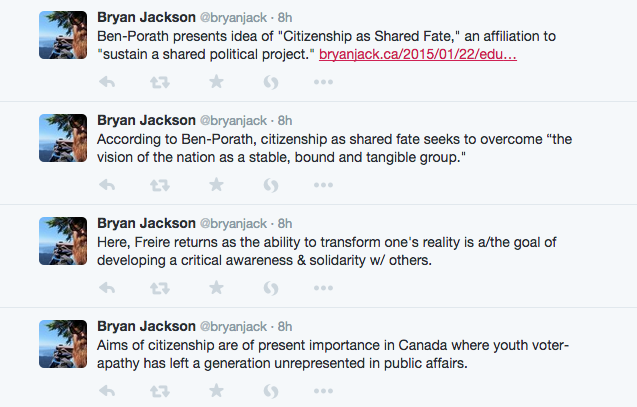

To confront this inherent tension Sigal Ben-Porath presents a notion of citizenship as “shared fate,” which “seeks to weave the historical, political and social ties among members of the nation into a form of affiliation that would sustain their shared political project.”

Again:

Ben-Porath describes “citizenship as shared fate” as a form of critical citizenship within which “the vision of the nation as a stable, bound and tangible group” might be overcome. For Ben-Porath, civic learning for citizenship as shared fate includes acquiring:

- Knowledge of fellow citizens,

- Skills to interact with them, and

- Attitudes that can facilitate shared civic action.

Such a conception of civic learning echoes the emancipatory praxis of Paulo Freire, for whom the ability to “transform one’s reality” was paramount in realizing freedom from oppression.

In terms of researching answers to these questions, I am fortunate to work with three different groups of young people that cover a broad spectrum of our school’s high school experience. Between our grade nine/ten gifted cohorts learning in a district-funded program and with access to a unique curriculum and ample classroom technology, a senior-level Philosophy 12 course that has functioned as an open online course now for more than three years, and the grades 9-12 elective #IntroGuitar course, public digital spaces and social media support various processes related to civics learning and students’ honing of their own conception of their individual and collective citizenship.

I am curious to see how these questions might be explored within and around these communities of practice – among students, teachers, and potentially parents or open online participants who are brought into the fray. As well, I am excited at the possibility such a collective inquiry might offer the creation of a lasting forum of autonomous voices coming together in the shared space of the public web.