While I attempted to introduce the new academic year in a blog post that wound up meandering into too many of my thoughts and feelings on the culmination of BC teachers’ recent strike action, here I intend to share my initial guiding interests and projects setting out into the 2014-15 school year. As I alluded to in my previous post on the dawning of September, I plan to continue my research into citizenship education as concerns digital pedagogy, curricular reform, and broader currents in educational philosophy.

In the last few years, I have become an admirer of Paulo Freire‘s notion of critical pedagogy, and try in my own practice, as well as my classroom constructivism, to create habits surrounding an ongoing praxis of reflection and action for myself and my students. Such a praxis suits the type of citizenship education Gert Biesta and others espouse as central to the emancipatory process introduced by Freire, and also aligns with many of the intentions of pioneers on the open web and in the digital humanities. In my work as an open educator this praxis also revolves between the theoretical concerns of pedagogy and the practical applications of these intentions.

Reclaim TALONS

One such foray into the practical application of my research interests has me finally setting out on an adventure I have long-anticipated.

Since taking the TALONS communities onto the public web, first with Edublogs.org, then Wikispaces.com and free WordPress.com sites, I have largely pursued a narrative of online learning which focused on the skills and awarenesses required in the digital sphere. Working across these public platforms, my students and I have contemplated digital citizenship and storytelling, as well as had many opportunities to connect our classroom learning with a wider audience than within the school district’s information silos.

Each of these services – Edublogs, Wikispaces, and WordPress, among others – have afforded us the opportunity to dip our toes in the public web without first surmounting the limits of my own technological expertise around how to manage and administer our own classroom spaces and domains.

But in the meantime, I’ve had the pleasure of getting to know and work with a handful of innovators in higher education who have shown me the relevance of gaining such expertise, both for my own development as an open practitioner, and as an opportunity for the students I work with.

But in the meantime, I’ve had the pleasure of getting to know and work with a handful of innovators in higher education who have shown me the relevance of gaining such expertise, both for my own development as an open practitioner, and as an opportunity for the students I work with.

In his 2009 essay, “Personal Cyberinfrastructure,” Gardner Campbell presented an idea Jim Groom, Tim Owens and Martha Burtis have since ran with at the University of Mary Washington:

Suppose that when students matriculate, they are assigned their own web servers — not 1GB folders in the institution’s web space but honest-to-goodness virtualized web servers of the kind available for $7.99 a month from a variety of hosting services, with built-in affordances ranging from database maintenance to web analytics. As part of the first-year orientation, each student would pick a domain name. Over the course of the first year, in a set of lab seminars facilitated by instructional technologists, librarians, and faculty advisors from across the curriculum, students would build out their digital presences in an environment made of the medium of the web itself. They would experiment with server management tools via graphical user interfaces such as cPanel or other commodity equivalents. They would install scripts with one-click installers such as SimpleScripts. They would play with wikis and blogs; they would tinker and begin to assemble a platform to support their publishing, their archiving, their importing and exporting, their internal and external information connections. They would become, in myriad small but important ways, system administrators for their own digital lives.3 In short, students would build a personal cyberinfrastructure, one they would continue to modify and extend throughout their college career — and beyond.

In addition to building technical knowledge and skills required to exercise agency and voice in the post-Gutenberg age, students charged with the creation and maintenance of their own personal cyberinfrastructure would be engaged in learning across the disciplines of “multimodal writing to information science, knowledge management, bibliographic instruction, and social networking.” To read Campbell’s 2009 call for this type of university education strikes me at this stage in my research and interest in the digital humanities and citizenship education as the intersection of the two, and something that ought be explored at the highschool level.

By Campbell’s description, this discussion of a technology-infused education, is everything at the core of popular discussions of digital skills, literacy and citizenship. “If what the professor truly wants is for students to discover and craft their own desires and dreams,” he writes,

a personal cyberinfrastructure provides the opportunity. To get there, students must be effective architects, narrators, curators, and inhabitants of their own digital lives.6 Students with this kind of digital fluency will be well-prepared for creative and responsible leadership in the post-Gutenberg age. Without such fluency, students cannot compete economically or intellectually, and the astonishing promise of the digital medium will never be fully realized.

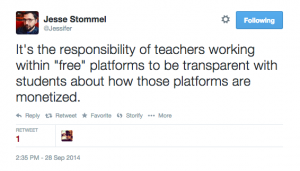

While Campbell admits that such forays onto the open web wait until students enter college, the intervening years in educational technology have only hastened the need for students to protect and manage their own data. In British Columbia, FOIPPA laws surrounding storage of student-data on locally maintained servers creates the need for many district’s and educators to work within closed or clumsy information management system provided by Pearson or Microsoft, where after spending millions for the software, the rights to the intellectual property of student work is retained by the company.

The same laws might be seen as the impetus for public school students in British Columbia to be educated in owning once and for all their digital selves, as it is in the interest of so-called ‘protection’ of this information that the laws exist in the first place.

The same laws might be seen as the impetus for public school students in British Columbia to be educated in owning once and for all their digital selves, as it is in the interest of so-called ‘protection’ of this information that the laws exist in the first place.

Since the University of Mary Washington launched its own riffs on Campbell’s cyberinfrastruture in projects such as Domain of One’s Own and Reclaim Hosting, I’ve often mentioned to Jim Groom that I would love to bring what he and Tim Owens and Martha Burtis have created to the TALONS classroom. For only my own hestiation has it taken this long to bring the project about though, as Jim has been enthusiastic about the prospect from the first. Within a day of sending Jim and Tim an email outlining where I wanted to go with the TALONS data, the class site had migrated to its new domain (http://talons43.ca).

The journey had begun.

In the week since, I’ve also moved the open course Philosophy 12 from its old WordPress digs to a subdomain on the same site (http://philosophy.talons43.ca), and will do the same with the school’s open Introduction to Guitar closer to the spring. Tim and I have begun to see if data from the class’ years’ old subject wikispaces will easily migrate to DokuWiki apps residing on the same site (eg. http://socials.talons43.ca), and in the next few weeks the TALONS will be setting up their own blogs as extension of the webspace which they will use to chart their learning over their two years in the program. When they come to graduate from the program, and move into grade eleven and beyond, they will have the opportunity to take their data with them, transfer it to their own domain, and continue in their digital educations.

As the province begins to etch out its vision of personalized learning, I submit what comes of our continued experiments to the discussion of citizenship education in the 21st century.